What the Vision Pro is actually for

Some speculation, based on over a decade of experience with AR & VR

Earlier this month, Apple announced the Vision Pro headset - their first dedicated device for AR (Augmented Reality) / VR (Virtual Reality) - hereafter referred to as XR - after several years of speculation and rumour.

The response has been mixed:

Mark Serrels at CNET branded the Vision Pro a ‘dystopian device for a dystopian world’, whilst Bryan Lunduke declared it a ‘device designed to make you less happy’.

On the other side of the fence, Mark Spoonauer of Tom’s Guide posted a review of his time hands-on with the device and concluded it is ‘truly amazing’, and Alice Clarke at Gizmodo wrote that it’s ‘the most immersive headset I’ve ever used’.

So, nothing new there then. Like all new tech, the Vision Pro has its detractors and its evangelists. Apple is entering a market that has been hyped beyond all reason, but one that has repeatedly failed to deliver on the breathless promises of XR acolytes going back decades. The most recent high-profile embarrassment for the XR industry was Zuckerberg’s poorly-executed ‘Metaverse’, which delivered little more than an annihilation of sensible search engine results about ‘the metaverse’ itself. Paradoxically, Meta is also responsible for VR’s greatest success story: the Quest; though one could argue that they simply had deep enough pockets to bring the Oculus hardware to an eager gaming market at a not-unreasonable price.

On the AR side of things, the most common method ‘normal people’ use for engaging with AR apps and content is still the smartphone, though big tech companies have repeatedly tried and failed to tap into a consumer market for wearable AR headsets. Google Glass - touted as the futuristic wearable we’d never leave the house with, is now kaput, and Microsoft’s HoloLens has found a rather niche home in the commercial sector, but no ordinary person is ever likely to buy one for home use.

You see, both AR and VR have a problem - and after spending the better part of my career working in the mixed-reality sector, I believe I understand what that problem is: the two are intrinsically linked, and cannot comfortably exist if one-half of the partnership isn’t present, or presented as an embarrassing second cousin.

The Problem With VR

VR headsets have found a reasonably successful home in the gaming market, and to some extent, the commercial market has found uses for VR in visualisation, engineering and architecture. Though devices like the Quest do not yet enjoy anything like the market share of say, the Nintendo Switch, it is undoubtedly the gaming sector which has driven VR to prominence in the XR landscape, and though the Quest is hardly rivalling a modern gaming PC for graphical fidelity and performance, it would be foolish to discount its place as a viable games console, which is, luckily, what most people view it as.

Unfortunately, gaming is not an ubiquitous pastime in the same way that, say, endlessly scrolling on a phone is - and so, just like Sony and Microsoft turned their games consoles into ‘media hubs’, there is something of a persistent push by VR companies to make their devices do ‘something’ that isn’t limited to gaming. The Quest Pro is pitched not as a gaming device, but as a ‘new way to work’. Its marketing essentially ignores its VR capabilities in favour of its passthrough mode (AR, to normal people). Meta wants you to see it as a device you’ll wear for a large percentage of your time, and, naturally, concludes that this means you want to use it for work. And that all of your colleagues will also want to use it for work, too.

It touts its support for Adobe Acrobat as an experience, rather than the ability to read PDFs.

Why would they do this? Given that there is almost nothing in the universe less exciting to ordinary people than the words ‘Adobe Acrobat’, why would Meta create a device, costing a cool £999.99, pitched so squarely at business users rather than recreational users?

The Quest Store’s ‘top selling apps’ page hints at the answer: the top selling non-game app is Virtual Desktop which, as the name suggests, allows you to use your PC or laptop in VR. For £15, and a few minutes of setup, you can connect your Quest to your PC, which means that not only can you stream PC-VR games to your headset, but you can also use any other software you already have installed. Obviously, there are constraints and limitations here - but the picture is clear: people want to do more with the Quest than Meta is currently offering: and they’re prepared to pay for it. They want to use it like a general-purpose device: something like a phone, something like a PC, but something altogether more than what it actually is: which is a VR games console that has a customer base whose ambitions far exceed the ability of Meta to deliver.

In this context, the Quest Pro begins to make sense. Correctly identifying that gaming is not enough of a sell to reach ubiquity, Meta aims the Pro at sensible people and businesses. Those who don’t really want to spend £300 to play games, but do want to spend £1000 to read PDFs and have meetings with cartoon characters of questionable ambulatory capacity. We all know somebody like that, right?

The advertised passthrough capability of the Pro, and Meta’s more general push in this area, also belies the prospect of VR-first headsets as the ubiquitous, mass appeal devices VR evangelists would like them to be. Without weighing too heavily on the social & ethical considerations of VR use, it is obvious to me - as somebody who both works with VR and uses it recreationally - that as humans we are simply not built for extended periods with a machine strapped to our faces, detaching us from our natural surroundings and those who happen to be around us. It is, except in rare, deliberate moments of shared play, with friends and family laughing at you waving your arms around in thin air, an almost comically antisocial activity. Idly thumbing through your phone whilst you have company is one thing: it’s quite another to metaphorically remove yourself from the room altogether in order to spend time in a virtual world.

Passthrough attempts to resolve this problem by giving the user the option of seeing the real world around them and thereby interacting with people whilst using the headset. Conveniently, passthrough also enables AR usage - where users can project apps into their surroundings, or augment their environment with information & utilities. When combined with the scanning technology designed for the device to accurately comprehend the physical environment in which it’s being used, the Quest Pro’s passthrough capabilities turn what is otherwise a VR headset into something which is intended to provide a more ‘natural’ feel.

In a kind of technological Catch-22: the solution to VR’s primary problems is AR.

The Problem With AR

Augmented Reality has a different, but possibly more serious problem. Most people’s direct experience with AR is limited to things like Snapchat or Instagram filters, the occasional game (Pokemon Go being the stand-out example here) or utility apps on a smartphone. Commercially, companies have offered AR software to customers for product visualisation (see what this sofa will look like in your living room) or simply for more overt marketing purposes (scan this QR code and watch our cool 3D advert). Artists have used AR to bring 2D artwork to life or build interesting 3D pieces that you can walk in and around. There is certainly an appetite for AR, and interesting and exciting use cases, but the current primary delivery mechanism - a small rectangle you have to hold out in front of you - doesn’t afford the same degree of flexibility and opportunity to developers to produce interesting, immersive software as a VR headset does. AR is also, therefore, usually an optional mode within specific apps that users must explicitly engage with, rather than an immersive, ever-present experience in the same way VR is.

Until now, the only commercially available AR headsets - the solution to this problem - are limited in functionality, expensive, and primarily aimed at fulfilling specific roles within a particular niche.

As a computing metaphor, AR suffers from extreme fragmentation. For most recreational users, there is no cohesive or coherent experience between apps. VR headsets come with an operating system, an app store, social features, customisable home screens, and platform-specific design guidelines. AR apps on phones implement a mish-mash of different features, wildly different interaction mechanisms, and extremely variable quality.

Although there have been several attempts to produce an AR headset which will help to solve these issues and bring some standardisation to the AR experience, none have yet made a significant impact on the mass market.

Enter Apple

Apple’s Vision Pro represents, despite the not-entirely-unwarranted mockery from some quarters, the most serious attempt yet at an AR-first headset which comes complete with well-defined user-interface guidelines, a sensible consideration for the headset’s place in the broader hardware / software ecosystem, and first-party support for integrating existing macOS and iOS software into a spatial computing platform.

Where the Quest and its PC predecessors established VR norms - the ‘way to do things in VR’ - the Vision Pro promises to do the same for Augmented Reality. If Apple’s marketing of the product so far is to be believed, then users can expect to hit the ground running with familiar apps from their phones and laptops as soon as they start up the device. Apple - despite the frustration it can cause developers, and the odd gap in quality or utility here and there - is famously opinionated about user experience and design; and their promotional videos around the visionOS interface suggest a similar look and feel to macOS and iOS, subtle gesture recognition, and direct integration with other Apple devices.

The decision to position the Vision Pro as an AR-first device is an interesting (but I would argue necessary) one for Apple to have made, given that the market here has so far failed to condense into something with even a potential for mass appeal. Unlike the iPhone or the iPod before it, there is no significant existing userbase of AR headsets for Apple to leap-frog. Most first-time Vision Pro users - whether they are simply trying the device out, or receive one from an incredibly generous Father Christmas - are most likely to have never experienced any kind of AR headset before, and so will be unable to compare it to other offerings. In some ways this is obviously an advantage for Apple - they will benefit from user familiarity with macOS and iOS, and if users are able to engage with the apps they’re already familiar with, then this will help to establish the norms and expectations that the AR experience requires. On the other hand, Apple is opening itself up to a potentially vulnerable position: it’s entirely possible that their assumptions about how users will wish to interact with AR software are wrong, and that a more nimble competitor may identify a more fitting user experience and force Apple to adapt, which could prove a costly scenario when a core part of the Vision Pro’s promise is standardisation and compatibility with their wider ecosystem.

The Vision Pro will be directly competing with the Quest Pro first and foremost - and though I would probably bet on Apple, I don’t think it’s a foregone conclusion that they will come out on top here.

The Quest Pro is, for one, significantly cheaper than the Vision Pro. It’s also most likely to appeal to VR enthusiasts who have already invested in one or more VR headsets and who are willing to spend more - but not too much more - on an AR equivalent. The attraction of the Vision Pro is in the raw power of the device, and its integration with the wider Apple suite of devices and software. Whereas I would imagine Apple’s primary customers for at least the first few years will be hobbyists and developers, the Quest Pro may, with time and some work, benefit from an established base of Quest users and provide a more affordable alternative, without needing to worry as much about the consequences of experimentation with interaction and UX.

Meta has not, at least in my opinion, invested enough in the operating system of their devices so far to provide the same kind of experience that visionOS claims to offer, but I would expect to see much more development in this area and a real push to provide compatibility with other devices and services, in order for the Quest Pro to remain viable as a direct competitor rather than a ‘lite’ version of an AR headset, or a VR headset with ‘some’ AR functionality.

Apple also stands to benefit from an army of developers, many of whom have already established a healthy income from macOS and iOS software, and who are familiar with Apple’s development ecosystem. Though the same could in theory be said about Quest developers - it’s worth considering that the Quest’s existing reputation as a gaming headset rather than a ‘spatial computer’ could mean that there’s a lower likelihood of non-game software being developed for Quest headsets in the first place.

Unification

Whatever the future of the Vision Pro and its Quest counterpart - one thing is clear: big money is being spent on closing the gap between AR and VR. Though I don’t get the sense that Meta has understood the need for this in quite the same way as Apple appear to have done, I see Apple’s announcement of the Vision Pro as their attempt to insert a crowbar into the space and to allow some light to shine on the fundamental problem: VR gaming and a sprinkling of AR / VR commercial applications is not enough, and a more general purpose offering is required if AR and VR are ever to reach a critical mass. AR-first headsets are, in my view, the way to achieve this: allowing people to remain oriented in the real world whilst using immersive software, and giving users the ability to tune the real world out as an option for things like games or other entertainment in VR mode (or something akin to it).

Even in the best-case scenario for Apple, the price tag of the Vision Pro means it’s unlikely to reach a critical mass for a number of years yet. For that to happen, the price will need to come down: particularly if Meta or another competitor manages to provide a comparable experience for a lower price. I suspect heads at Microsoft are currently being turned back towards the HoloLens too: it is not beyond the realm of possibility that a much more consumer-oriented HoloLens appears in the not-too-distant future.

The key thing that Apple - and to a lesser extent Meta - is offering is the unification of AR and VR. AR-first headsets are likely to remain a hobbyist or luxury purchase for a while yet, but Apple has plenty of money to throw at the hardware and software for a good number of years in order to create the market it appears to believe will exist. This is not without precedent for Apple: the Apple TV (the hardware) successfully bullied its way into enough homes to justify the creation of Apple TV+ (the streaming service) - which now competes directly with other major streaming services and has helped to broaden Apple’s ecosystem.

Where the Quest Pro is pushed along by its VR cousins, the Vision Pro is attempting to meet it from the other direction: by providing a fully fleshed-out AR experience with a smattering of tasteful VR features. The natural convergence point still lies some way off - one device that can do both AR and VR well, and seamlessly - but as a longtime user and developer for the XR ecosystem, I’m happy to see that something I’ve felt was needed for many years is now being addressed by companies with deep enough pockets to make it happen.

Whether or not a market for AR-first headsets is viable remains to be seen. Despite the jokes about Apple’s dystopian future vision, and that stupid, stupid ‘look at my eyes!’ feature, it’s clear that Apple is willing to shovel more money than you or I are ever likely to see into this potential pit, and I doubt they’re doing it for a laugh. The prospect of spatial computing has long been the stuff of sci-fi, but in the Vision Pro, we, at last, have the first glimpse of what it could look like with a serious, consumer-oriented approach.

If my gut is correct, and Apple does manage to pull this off over the long term, then I believe spatial computing will establish itself as a much more accessible and natural-feeling way to engage with modern technology than we can currently imagine. Ignore the bulky and ridiculous headsets for now - nobody wants to wear something like that for any serious length of time - but focus instead on the combination of hardware and software. Establishing spatial computing as a viable proposition for ordinary people is, I believe, going to be a long-term project, and though there are plenty of reasons to worry about the worst-case scenario of a world where we’re looking through each other rather than at each other, there is also reason to be optimistic. It’s not difficult to imagine that gaze & speech could be a more accessible alternative to the disabled and infirm than tapping on a screen or moving a mouse - and the potential for contextually-aware assistance and information without the need to hold up a phone seems to me, at least, an attractive proposition.

Vindication

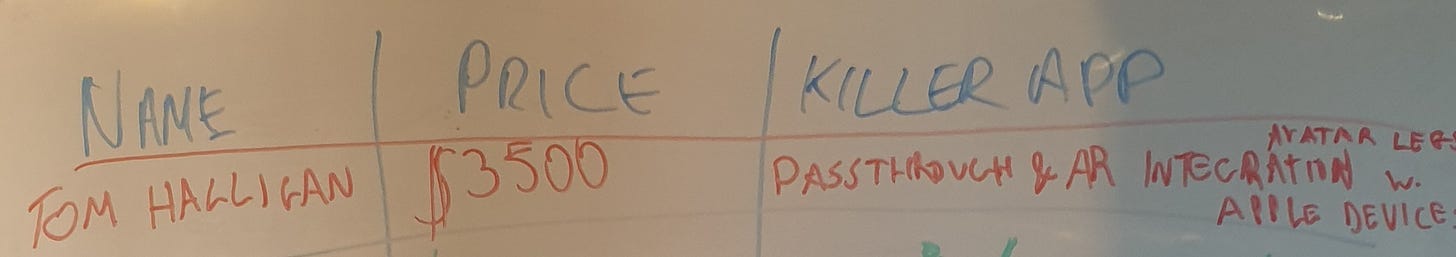

On the day of Apple’s announcement, my workplace held a WWDC watch party. As part of the proceedings, and because rumours of Apple’s announcement of some kind of headset had become something of a relentless background noise, we decided to place bets on the price and ‘killer app’ of whatever was announced. I’m happy to say, dear reader, that I absolutely nailed it, aside from the apparently impossible dream of ‘avatar legs’, which remains, for now, an elusive goal even for tech companies with infinite money. You’ll have to forgive the handwriting: it turns out writing on a whiteboard is not a skill I possess.

Ultimately, only time will tell whether the Vision Pro will be a success. I’m certainly feeling rather smug at my accurate prediction for where Apple was heading with the Vision Pro, but, if it all comes to nought, then I will take comfort in the fact that I was only as wrong as Apple were - and that it didn’t cost me several billion pounds to find out!

"sensible people and businesses. Those who don’t really want to spend £300 to play games, but do want to spend £1000 to read PDFs... that, for some reason, are just flattened JPGs in a PDF container that's been compressed to hell so it could be emailed"

That said, I do kinda wonder how lo-res stuff will look

That's a great comprehensive explanation and assessment Tom. Vision Pro and XR look "interesting". But not so interesting as to instil in me an irresistible urge to spend that much money on an Apple device. Might be my age. There just isn't a Vision Pro shaped hole in my life, so far!