Shattered Silicon Part 2: Broadcast Culture

The future will be built by the do-ers, not the say-ers.

Introduction

In Part 1 of this series, I described a problem I see in modern technology: the Tyranny of Simplicity - wherein the shift to digital services and products has stripped away the capacity of our institutions and companies to take into account the subtlety and nuance that defines human interaction.

Shattered Silicon: Part 1

Welcome New Readers! Before I continue with today’s post, I’d like to welcome the influx of new subscribers I’ve had over the past few weeks. It’s been around a month since I had my 100th subscriber, and since then I’ve been averaging a handful of new readers every day. Thank you to everyone who’s taken the time to subscribe, share, and engage with my wo…

Here in Part 2, I describe another problem which, left unchecked, threatens our ability to take ownership of the technology we use every day.

Broadcast Culture

You don’t have to look very far to find people bemoaning the state of both offline and online media, the dangers of social media, or the risks of sharing your entire life online - it’s evolved into a self-perpetuating machine at this point: talking heads or anonymous posters lambasting one another for being wrong about everything, offending everyone, and ruining society, the planet, minds, lives, and everything in-between. Regardless of the subject, whether it’s politics, business, health, welfare, entertainment or even just mundane personal preferences, there is absolutely nothing more certain in the 21st century than the fact that if you can think it, you can waste an entire day arguing about it on the internet.

We’re probably all guilty of this tendency, to some degree - and there’s always plenty to talk about - so we can be forgiven for succumbing to that most basic of human impulses: the desire to be heard. God only knows how much time I’ve spent arguing with people I’ll never meet, or getting into lengthy debates about topics I can barely even recall today. However, I’m increasingly realising that our time on this earth is better spent doing rather than saying. For many people - particularly those who are not naturally interested in technology itself - modern devices and the internet have become more akin to a broadcast medium than the tools of human liberation and emancipation that I believe they can - and should - be. Despite the enormous power and potential which is literally at our fingertips, many millions of people experience digital life as though they are compelled to either drown in an ocean of noise or to stand alone atop a mountain of opinions, hurling them pointlessly into the valleys below.

I am increasingly convinced that the ‘talking’ parts of the internet have largely been a stagnating force on humanity, despite all of the good that can - and does - come from communication. I believe it would be infinitely more useful - both on an individual level and the more abstract societal level - if people were encouraged to do more rather than to speak more. As the saying goes - talk is cheap. We have tools at our disposal to create things our ancestors couldn’t have begun to dream about - yet we all too often spend our time receiving or broadcasting, rather than building.

In How To Actually Use A Computer I aim to provide some practical information about how we can choose to exploit the raw power we have at our disposal: to improve our own lives or the lives of others, rather than simply scroll through endless opinions, arguments, and debates. It’s difficult - no doubt about it - to motivate yourself to act on the goals and dreams you harbour within, and there’s no shame in using technology for entertainment or to relax and kill some time; but we should also try to keep in mind the sheer potential afforded to us by the devices that have become a fixture in our lives.

How To Actually Use A Computer #1

The internet today is creaking under the weight of a seemingly endless barrage of auto-generated clickbait articles, irritating website design, and next-to-useless search-engine results. Even when Google does manage to surprise you with a relevant result, there’s a high chance that the website you end up visiting will attempt to sell you thirteen differ…

Whether you want to educate yourself, build a product, open a shop, create art or entertainment, offer a service or share knowledge and insight - there has never been a time in all of human history when it’s been easier to do so. Where once you would have needed to physically travel to meet potential partners or investors, you can now communicate directly without leaving your house. Where you might previously have needed to hire a team of people to bring your vision to the ‘proof-of-concept’ stage, there’s now a good chance you can do much of the work yourself - or at least for a fraction of the cost both in terms of time, and money. AI tools and services are already being utilised to kickstart people’s ambitions and creativity, turbo-charging the ‘force multiplier’ effect that technology has brought to our fingertips.

Ads Infinitum

Unfortunately, in the digital world (and, in fact, the real world), attention is a battlefield. Adverts are constantly shoved in our faces, algorithms assess our behaviour and drive content to us that we are likely to react or respond to, and huge companies gently corral us into analytically convenient demographics and offer us apps and products which they believe are a good ‘fit’. We lap it all up: after all, if it didn’t work, nobody would bother wasting time and money doing it!

There is an enormous market for your information: your likes and dislikes, your attitudes, the things you buy, the places you visit, the people you communicate with, and your browsing habits. What we often perceive to be passive, harmless activities online have become, for years now, a vehicle for others to become extraordinarily wealthy through the simple act of recording and then selling information about us.

Though it’s common to find criticism of ‘consumer culture’, I would argue that ‘broadcast culture’ is a major enabling factor: something we virtually all engage in either actively, by sharing our views and opinions publicly, or passively, via the simple act of existing in the modern digital world with all of its trackers, analytics, surveillance and subterfuge. Advertising is the lifeblood of the digital world, and virtually everything you do online is designed, one way or another, to either push ads to you or extract information from you that can be used to work out which ads to push to you.

Whilst taking a break during the writing of this post, I read “Machine Killer”, by

of Hit Points, a newsletter about the videogame industry.Nathan discusses the problem of ‘the web’ being driven by advertisements and the effect this has had on publications - and also touches upon a new revenue-damaging ‘feature’: Google using AI to provide a summarised response to user’s search queries:

This model may work for Google, and Google users, for games that are already on shelves. If someone searches for advice on Cyberpunk 2077’s Dex vs Evelyn decision in 20 years, Google’s ML models will be able to provide it. But what about the games of the future? What are you going to train the machine-learning models of tomorrow on when you’ve put all the guides teams out of work, the websites they used to write for have gone out of business, and no new ones have stepped into the void because you’ve shown there’s not a penny to be made from producing content for Google’s robot army to steal?

In many ways, broadcast culture - our tendency to share, whether knowingly or not, vast quantities of information about ourselves - has enabled the AI revolution which is currently taking place, and which now threatens publications like those that Nathan mentions. ChatGPT and other AI tools know how to talk to us precisely because we have, for years, poured anything and everything into their training data. Some services are now providing ‘opt-out’ capabilities so that you can choose not to have your data used to train AI models - an admission that broadcast culture is intrinsic to the business model. There is an assumption baked into the digital economy that there’s a free-for-all on your data and the words and works you produce. Even if you are not actively trying to make a living online, someone is almost certainly making money off your digital footprint, and to ensure that they can’t is to take part in a time-consuming, complex, and ever-escalating arms race against behemoths with infinite money and great influence over the technology you use every day.

From the perspective of the companies harvesting and trading in the data and information we leave in our wake, there is a resource which we, as humans in the digital era, can’t help but produce in vast quantities. Since this resource is not bound by national borders, these companies have erected their own, and marketed them back to us - and regulators - as ‘privacy controls’, all the while tailoring their software and services in such a way as to encourage us to produce even more data, to broadcast more information about ourselves, and to stay within their borders. Keeping you ‘on-site’ is a major ambition for services like Facebook, which goes a long way to explaining the scope creep of what was once a glorified contact list.

If, in the early days of the internet, we had decided that actually, we didn’t really mind paying for things like search engines and services like Facebook, then perhaps the reliance on ad revenue might not have had such a stranglehold over the digital economy, which in turn may have resulted in the internet being shaped in a different mould than the one we currently have. Companies may have been incentivised to encourage you to pay more rather than to say more - and in turn, perhaps social media platforms would have been designed to provide value to the customer, rather than being designed to bait users with outrage and division in order to keep them engaged and producing data for advertisers.

The Remedy

Whatever shape the internet takes in the future, it’s clear that something is changing. AI tools and services are already driving a wedge between creator and consumer, and even wannabe Bond villains like Elon Musk seem to acknowledge the writing on the wall, turning X (formerly ‘The Hellsite’ or ‘Twitter’, to non-users) gradually into a paid-for service. Whether that works out for him or not remains to be seen - but it’s at least a change that his competitors haven’t been particularly keen to embrace for the time being, reliant as they are on their free users churning out endless data.

Other services - such as Substack - are going with a business model that actively promotes a more traditional ‘get what you pay for’ style of social media: users can subscribe to the writers they like, and pay for those they want to support. It’s up to writers to market themselves and to determine their pricing and what users get when they do subscribe. The fact that this is often presented as some kind of ‘new’ business model is very telling - and reveals just how bizarre the digital economy (and, to an extent, the legacy publishing and journalism industry) really is. The only way Substack’s business model could be more traditional and ‘normal’ is if writers had to build a brick-and-mortar shop to sell their wares.

Social media platforms themselves are diversifying: the new buzzword in social media circles is ‘federation’: a set of protocols and systems which enable users to draw content from, and publish content to, a multitude of sources. Services are loosely connected via protocols which allow individuals, if they are so inclined, to more carefully isolate their information and ‘own their own data’. Networks like Matrix and Mastodon enable users to self-host their own ‘home server’ - and then connect it to any number of external servers depending on the content and communities they choose to interact with. This is in stark contrast to the bigger, centralised services which currently dominate the landscape, forcing users into a walled garden in which the content they consume is more carefully curated than they might suspect.

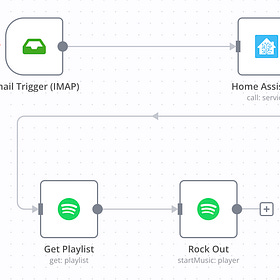

In Self-Hosting Shenanigans, I explained some basic approaches to self-hosting services and tools, and will return to the topic in the future to demonstrate how we might do the same for social media services.

Self-Hosting Shenanigans

I’ve been thinking recently about self-hosting - running your own servers and services to suit your needs and facilitate your personal and professional life. In an era where technology creeps into our homes from every angle (even the humble doorbell is now an internet-aware communications device!), it seems to me that seeking to coalesce and control thi…

A common theme in the ongoing shift in digital services is a return to deliberation alongside an enormous evolution in the arena of curation. Whether you are producing or consuming, or a combination of the two, we appear to be arriving at a fork in the road. We can choose to accept the digital landscape as it is: a handful of massive companies providing ‘free’ services in exchange for our data, or we can choose an admittedly ‘messier’ path, but one which affords more control, in which we as individuals take it upon ourselves to commit to the things we actually care about; to put our hands in our pockets to support the things we value, and to unshackle ourselves from ‘the algorithm’ which determines who and what we see based on the whims of people and businesses we have no relationship with, in favour of more carefully considered connections directly to the people, businesses, and communities we are interested in.

If we don’t take the second path, then the future is likely to look very much like the past - ever more tightly controlled, curated by unseen algorithms, and funnelling profits into the hands of those who deserve it least at the expense of your identity and privacy.

It’s unlikely that the tendency for online companies to trade in our freely provided information will go away overnight, but it seems to me that we can take practical steps right now to detach ourselves from such a pernicious business model and start to take things into our own hands.

Whether you run a business, write, build products or services, or just use the internet for entertainment, we should try to remember that we have more power than it might appear, and with a little work, we can establish ourselves today much more easily and effectively than our analogue ancestors.

When it comes to social media, we should consider more carefully the value we get from adding our voices to the maelstrom, and the value we get from listening to people who speak a lot and say little.

At your fingertips, right now, is a device which - with a little care and consideration - can empower you in ways you might never have considered. It’s your choice how it’s used, but I hope that we collectively choose to do more than we say, to create more than we consume, and to take back control where we have ceded it to those who have profited enormously from our great online experiment.

A return to the Wild West of the digital era is looming, I believe - and it will be hastened, for good or ill, by the advent of viable AI tools which shake up our relationship with the tech behemoths we’ve become accustomed to relying on. Our job, as curious, creative apes, is to identify and embrace what it means to be human in an age where the way we interact with the digital world is rapidly changing. We are the builders, and we get to choose.

Thanks for reading! Feel free to share this post, and if you’re not already subscribed, hit the button below. Any subscription at all is appreciated, but a paid subscription helps me to write more regularly!

In Part 3, I’ll discuss the third, and possibly the biggest, problem with our modern world - one which is only going to get worse with the proliferation of AI tools and services: A Skill Issue.

The web enabled the perpetually outraged and the perpetually fearful, and has never looked back.

Yes, the great irony of Substack, the one shilling subscription model of ye olden days. 😁