I'm not asking you, I'm telling you. These creatures are the only sentient race in the sector and they're made out of meat.

- Terry Bisson [They’re Made out of Meat]

Humanity has long struggled to reconcile its differences. Across borders, faiths, cultures and time itself, we’ve invented uncountable and unfathomable punishments to mete out against one another; to wage war against the barbarians, the heathen and the alien. Though we often like to think that we in the modern era are more civilised, peaceful, and more enlightened than those in the ignorant past, you don’t have to look very far, wherever you may be in the world, to find bigotry and violence being played out over and over again.

“Wouldn’t it be better”, goes the common lament, “if we could all see that underneath, we’re the same?”.

This idea is attractive; if reductive. We are all the same in some sense: we’re made of flesh and bone, and we all need shelter, food, companionship and comfort. We all lose something of ourselves when our basic needs aren’t met - we may become harder, more prone to aggression or anger, or we may become depressed, more sullen and reclusive. In that respect, we share a common human experience. And yet, we stand alone. Our thoughts and emotions stubbornly defy our ability to express them. Our internal worlds are as rich and varied as the earth beneath our feet, but our ability to convey ourselves to one another is fraught with danger and ripe for misinterpretation.

Behind every great text is an author frustrated with their inability to find the right words. Every canvas invites the artist to describe - but not quite - their vision. Every soaring orchestral masterpiece is a scream from the soul of the composer: please understand, please hear me.

We are all the same; we are all islands, trying in vain to build bridges.

The Tower

“Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language, and this is only the beginning of what they will do.”

- Genesis 11:5–7

Most of you will have at least some passing familiarity with the story of the Tower of Babel. For those who don’t, the story goes something like this:

Humanity, united after the flood (of Noah fame), and sharing a common language, decided to build a great tower up to the heavens. God, seeing this, and being affronted by their pride, decided to destroy the tower and decimate their ability to speak to one another, resulting in the varied languages and cultures we see today.

Putting the theological considerations to one side, it’s not difficult to imagine the potential positive implications of a world where all of humanity spoke a single language. If you’ll allow the indulgence - surely we can agree that fewer opportunities for confusion and more opportunities for collaboration would result, at least in theory, in a more pleasant and cohesive society? Obviously, this is a wild oversimplification - we would still, of course, find reason to disagree - but a common language would allow us, despite its imperfections, to at least share our thoughts more easily with one another; to work together and to navigate the world in confidence.

Instead, we are condemned to our imperfect reality: we must work to convey meaning to one another, to overcome differences in language and culture in order to make progress and find peace. Our internal world, too, must be translated into some approximation of its true meaning. We condense our intangible thoughts and feelings into wet ink on a dry page; forever trying and, often (if not usually), failing to capture it perfectly. How arrogant were the ill-fated builders of Shinar, to believe they could reach the heavens, when we, as humans, can’t even reach each other?

Talking to The Machine

In a post-Babel world, humanity has stumbled through to the modern era relatively unscathed. We haven’t, as of yet, annihilated ourselves (though we’ve come pretty close), and we’ve done a pretty good job of connecting to one another and overcoming our language barriers. The age of the internet has arrived in all its glory, allowing people separated by entire oceans to speak freely with one another, aided by translation tools, the ability to share art, music, poetry and pictures. Never before have we had the means to express ourselves in such a varied and complex manner, and to reach such a wide audience. If God is real, they must be absolutely furious. A tower to heaven is one thing, but animated GIFs? Surely, we’re due for a smiting.

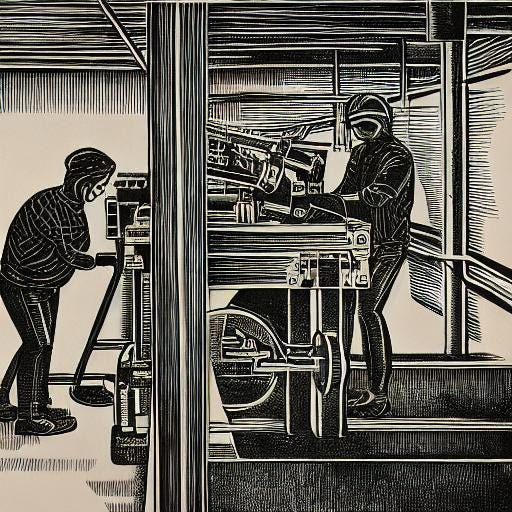

This technicolour dream would be impossible, of course, were it not for the humble computer. Where once we may have been restricted to the spoken word or the written page, we are now unencumbered by audible distance or the physical medium; our thoughts now massaged into electrical impulses via the tap of a keyboard, squeezed into cables traversing the sea floor, blasted into space, beamed back down again, and transmogrified for consumption by hungry eyes and ears, to millions of people, at the speed of light.

All of this is made possible by an emulation of God’s wrath against the architects of Babel’s tower: a myriad of programming languages, utterly foreign to the vast majority of humanity - yet several orders of magnitude less complex than the languages we speak and think in daily - bridge the gap between man and machine, constantly evolving and improving, bringing us ever closer together and yet still, somehow, keeping us as distant from one another as we’ve ever been.

As we’ve introduced machines to the world, and sent our thoughts and dreams off, hitched to a thousand digital wagons, we may have inadvertently set ourselves on a path to increased isolation and separation from the natural world and, by extension, each other.

The internet is awash with subcultures and micro-communities, each with their own lore, history and dialects. We are freer to communicate than ever before, and as a result, the breadth of our human languages has grown enormously whilst our mastery - our ability, or even our will - to express what we actually mean to one another, seems to diminish in the face of the sheer volume of information we are confronted with.

Rather than finding the words to express derision at a corporation’s latest fumbled attempt to appear like a relatable human, we post pictures of a crab shooting lasers from its eyes. Instead of congratulating somebody for some achievement in their life, we send them tiny icons of cartoon people with party hats. For all the rich possibilities we have at our disposal, it’s often the case that we find humanity wading in the shallows, rather than diving into the depths.

In a post on

, writes beautifully on the problems we may face in conveying our thoughts, feelings and senses to one another, particularly in the fast-paced, digital town square. The full post is worth a read and a subscription, but this passage sums up ‘the problem’ neatly:An abundance of words, of course, does not necessarily imply an interesting and compelling diversity of words. The quantity of words does not guarantee the quality of what is said. We encounter a mass of words, but it is a stark and monolithic mass, composed of abstractions, generic terms, and words that have lost their power to convey a distinct sense to the imagination. We’ve asked too few words to do too much, and now they are tired.

Despite our new-found capacity for communication, we often resort to babbling at each other, saying little of any worth or consequence. We mistake quantity for quality, whilst our inner being, in its lifelong struggle to be seen, heard, and understood, compels us to keep scrolling, to keep posting, and to keep consuming. Surely, somewhere in all this noise, we will find that spark of connection: the acknowledgement, at last, that we are here, part of this world.

The Machine Talks Back

Out of the maelstrom emerges a new presence. The tech world, and increasingly the wider public, is getting to grips with what we have tentatively described - though opinions vary - as Artificial Intelligence.

Though the technical limitations are still a fair way off from the kind of all-knowing, all-seeing AI you might see in a sci-fi film, the current iteration is still compelling and impressive to all but the most cynical among us. Those who don’t know or care about how it all works are often amazed or alarmed in equal measure at the experience of ‘chatting with an AI’. Even those who do understand the technical specifics are impressed at how human-like the experience can be. In stark contrast to the incoherent jabbering that has come to dominate online interaction, we are now seeing people sharing with astonishment the unconscious hallucinations of machines. From poetry to academic articles, long-form essays, images, and music, the online world is awash with humans obsessing over the creative output of a system which cannot even comprehend their existence, let alone it’s own.

We are witnessing a fascinating phenomenon - expression-by-proxy. People who haven’t written so much as a haiku are finding joy and at least some degree of fulfilment in compelling a computer to produce for them the poetry they would write, if they could. The picture they would paint, if only they could master a paintbrush. This is not to diminish the pleasure they find in exploring the possibilities of AI: it is certainly fascinating, and it’s a tool like any other. Who am I to criticise anybody for how they express or entertain themselves?

“Electric muses

Robots crafting verse sublime

Artificial soul”

- ChatGPT

There is, I believe, something fundamentally interesting about instructing a machine to do something for us. Those of us who are programmers by trade or hobby are familiar with the particular itch being scratched: making a computer bend to your will opens up a world of possibilities. As a programmer, I find the new wave of AI interest to be enthusing and absorbing. The possibilities of AI writing computer code, rather than raising concern for my place in an industry that is already incredibly fast-paced, have instead opened my mind to any number of potential projects and opportunities.

Indeed, it is AI writing code which has led me down the philosophical avenue which inspired this post. For decades, the ability to instruct machines has been relatively tightly constrained to a small number of people who actually use those machines. Programming is complicated - and it takes a long time and a lot of practice to become proficient. Over time, new tools are produced which make programming easier and faster - which in turn results in ever more complex systems, and a greater number of things to learn and master. The complexity grows, even if the accessibility improves. New programming languages are invented - often to suit very specific technical tasks, but also to facilitate more general use cases.

In a paradoxical way, learning to code has never been easier than it is right now, whilst the sheer scale of possibilities means it’s increasingly difficult to master any particular area. We have, in the tech industry, become incredibly expressive when it comes to making computers do what we want them to do. And, in turn, we are now beginning to see that expressivity turned back on us, and humanity at large. We exist in a time where humans can write or talk in their normal, spoken language, and software, written in a technical programming language, can parse that input, reason about it, and then provide a convincing response as though a human were providing it, or accurately perform the tasks demanded of it. To be clear - it is not the case that this response is fool-proof. There are often errors or inaccuracies, occasionally incoherent responses or outright fabrications; these are technical quirks of the systems we have built so far - but to deny that something very impressive is going on would be silly.

This new ability to converse with the machines seems to me to be at odds with how we have become accustomed, in the digital realm at least, to conversing with each other. We are fascinated by a machine’s ability to produce a coherent, articulate response, whilst person-to-person interaction is often typified by short, abstract messages which convey little, if anything, of our true thoughts and feelings. We imprison ourselves, trained to keep responses short and snappy, or to fit within some character limit, whilst we actively encourage machines to produce lengthy, thought-provoking essays and beautiful works of art.

Hello, Computer

If you’ll join me in a thought experiment, perhaps I can imbue you with the same curiosity that has been aroused in me by the bizarre state of affairs we find ourselves in:

Imagine that humanity continues to improve on existing AI systems. It’s not a huge leap of faith to predict systems which will be able to comprehend human instruction given in natural language and produce consistent, quality responses - whether that is to respond in kind (i.e. to reply as a human would, or to produce some output - say - a picture) - or to act on our behalf and perform some task (e.g. plan out your meals for the week and order all of the ingredients to be delivered to your door). Let’s assume, for the sake of this experiment, that humans will come to use AI more and more; that we become accustomed to speaking and writing to machines, rather than tapping on buttons in user interfaces.

I wouldn’t assume that it’s a foregone conclusion that AI systems will merely continue to adapt to human expression. Instead, I would consider it highly likely that humans will learn how best to talk to the machine; that we would, in tandem with improvements in natural-language interpretation in AI systems, begin to adopt dialects that produce the best results for our needs. We already see the beginnings of this in the growing micro-industry of prompt engineering - where people structure natural language in such a way that it produces the desired response from an AI system. Humans are remarkably flexible when it comes to our ability to transform our language and expression to fit a particular context; what happens when we are subsumed in an ecosystem driven by AI? It’s likely that all widely-spoken languages will quickly become valid inputs to these AI systems - and the AI will be able to freely translate between languages as required. It is not certain, by any means, that AI will be able to successfully interpret any natural language instruction any more so than humans can successfully understand each other today, rife as we are with misinterpretation and imperfect clarity; so humanity will be forced to adapt to the machine, rather than the other way around.

Imagine, then, a world in which AI systems can successfully parse a reasonable - if contextually modified - input, in any language, and produce a valid, coherent response, or act in some way on our behalf. A world where humans, driven by the progressive encroachment of technology into all aspects of our lives and work, are compelled to adapt to the demands and constraints of the machine; just like we adapted to the keyboard and mouse rather than the handwritten note, and modify our language so that we may continue to function effectively in our societies. A world where personalised AI learns and reinforces the habits and predilections of the individual; where we need to spend less and less time engaging with the wider world and each other, because it has become trivial to have ‘the system’ do whatever we need it to do. A world where the machine is vastly more capable of articulating our thoughts and desires than we can possibly hope to be - constrained, as we have become, by the need to express ourselves in a way that the machine understands, rather than a way that unburdens the soul and conveys the meaning in our hearts.

What then, becomes of language, when it is no longer the sole domain of humanity? When, as a species, we share a common tongue with machines, rather than writing code for their consumption, are we losing something vital? When we learn to express ourselves in a way that machines understand, because that is what our modern world will demand of us, will we retain our ability to talk to each other, or will our language retreat, evolving into something more akin to a programming language? What happens when the relationship between man and machine is inverted: when the machine acts as interpreter between humans who are no longer capable of expressing themselves to one another? We may become vastly more capable of achieving any number of things thanks to the progression of technology, but the cost of every person becoming masters of their domain may be beyond our comprehension.

When we have 8 billion people who cannot talk to each other, and a machine that can talk to all of them, what does humanity look like? Are we building an inverted Tower of Babel - an impossible number of individualised, personalised dialects specialised at communicating with a single machine? What then becomes of our soul and our spirit - that individual, internal world - already imperfectly expressed by the full gamut of language, art, and emotion we’re capable of?

Are we building bridges, or walls?

Lighten Up

I am, contrary to the tone of this post, not an alarmist about AI. I fully admit to indulging in hyperbole here, and I don’t believe that things will ever become quite as bleak as I may have imagined above. I find it an interesting exercise to let my imagination wander with these things, and to mull over the philosophical implications of ‘worst-case’ and ‘best-case’ scenarios. Realistically, we will probably build AI systems that comically fail to interpret our demands for a long time, even if steady progress is made. The way we interact with technology will probably change quite rapidly, I suspect, and there will undoubtedly be changes in our societies as a result. I am hopeful, however, that the consequence of more ‘natural’ interfaces with computers will result in a revitalisation of human communication, rather than the opposite; since we will ‘need’ to spend less time at computers, or tapping at screens, and will therefore have more time to look up, at each other, and talk.

If we can re-discover what it means to communicate in natural language, perhaps our motivation to seek validation in likes and comments might subside a little. Perhaps the consequence of machines responding to us in well-written, articulate prose will be that we, in turn, rediscover the waning art of self-expression.

Whatever the long-term consequences of these changes will be, what’s certain is that we will be gaining an impressive toolkit with which to influence our world, to create and to learn; and with this ambitious arsenal, it’s my hope that we can conquer any number of problems.

Obligatory Parting Horror

It would be remiss of me not to mention one of the primary inspirations for this post -

by Paul Kingsnorth. We could not be further apart in our attitudes to technology, but Paul's 2-part essay beginning with The Universal stuck with me for days after reading it, and I would certainly recommend reading and subscribing. A teaser of the creeping horror you may find within:Imagine, for a moment, that Steiner was onto something: something that, in their own way, all these others can see as well. Imagine that some being of pure materiality, some being opposed to the good, some ice-cold intelligence from an ice-cold realm were trying to manifest itself here. How would it appear? Not, surely, as clumsy, messy flesh. Better to inhabit - to become - a network of wires and cobalt, of billions of tiny silicon brains, each of them connected to a human brain whose energy and power and information and impulses and thoughts and feelings could all be harvested to form the substrate of an entirely new being.

You should definitely pay him a visit - you won’t be disappointed.

Very interesting read - thank you for sharing.

A couple of points. I think some of what you have described has already transpired. ‘AI’ has not so much arrived as we have awoken to it. Social media has been a giant interaction between ‘AI’ and humans which I believe has coarsened language, although perhaps added some clarity and concision. Trump is quite a good example of the degradation of language, even though I realise his ascent was not purely due to social media.

My second point, I would not refer to AI as a tool. My interpretation of a tool is a technology that is fully understood by the person using it, and does not encourage a particular behaviour. A knife fits this definition: it can be used for cooking or murder. The choice is entirely down to the person using it. AI is understood by few people - perhaps nobody - and influences the behaviour of its users (e.g., social media).

If I prompt an artwork, I consider it vain to imagine I created that work in any meaningful way. The greatest effort came from centuries of artists whose work is being used by the system - which makes me object to the word artificial. Then there are the programmers who created the system, who have a huge influence on the output. Only after this does the prompter enter the equation, and I’d consider them of limited significance.

Have you read The Machine Stops? I came to this short story late, but it strikes me as very relevant to the scenarios you are writing about!

If we compulsively wish to see machine intelligence and robots in our image, what happens when the reverse occurs? As digital consumption increased on mobile phones increasingly and our habits became increasingly trained by, over the past decades one does wonder what generative AI will do to us? Given how people are using chatGPT one can already tell..... What is the new version of the infinite scroll instead of those favorite apps going to be? How will it further interrupt our humanity, socialization and capacity for human intimacy?